HomeNews & Events2022November In the Service of Canada:...

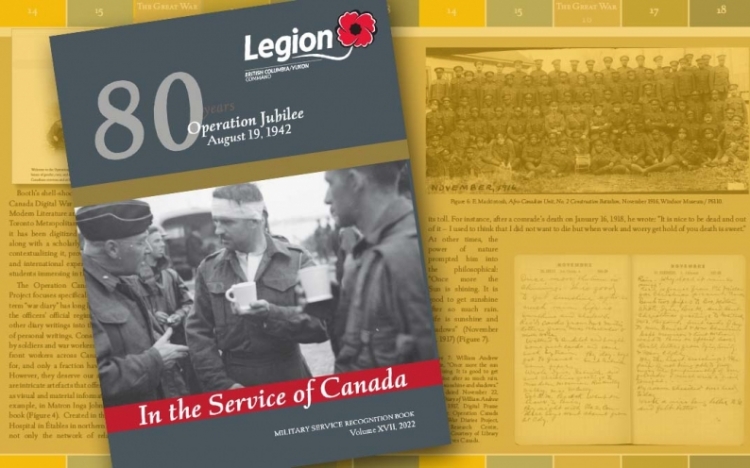

For Remembrance Day, the 2022 edition of In the Service of Canada, a preeminent Military Service Recognition Book in Canada, has recognized “The Operation Canada Digital War Diaries Project,” our SSHRC-funded study on Canadian World War I diaries with an essay written by Dr. Irene Gammel with research assistance by Cameron MacDonald.

Diaries behind the frontlines of war include the writings of doctors, nurses, orderlies, and chaplains. For example, the Operation Canada Digital War Diaries Project gives readers full digital access to the unpublished diaries of Reverend William Andrew White (1874-1936), a Black Canadian chaplain born to former slaves in Virginia who moved to Nova Scotia at the age of twenty-five and attended Acadia University before being ordained as a reverend in 1903. On February 1, 1917, at the age of 42, he enlisted in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-black segregated unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The only Black officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I, Captain White was also the only Black chaplain who served in the Canadian or British forces during the war. For the first time, the Operation Canada Digital War Diaries Project gives access to his voice, thoughts, and experiences.

White kept two diaries while he served in Europe with the No. 2 Construction Battalion, and his writings often reveal the intersection of war with race and religion. White critically references the racist second-class treatment of the “coloured boys,” who were often accused of “faking” illness. He also provides snippets on his weekly Sunday sermons, but despite his faith, the experience took its toll. For instance, after a comrade’s death on January 16, 1918, he wrote: “It is nice to be dead and out of it – I used to think that I did not want to die but when work and worry get hold of you death is sweet.” At other times, the power of nature prompted him into the philosophical: “Once more the Sun is shining. It is good to get sunshine after so much rain. Life is sunshine and shadows” (November 22, 1917).

The voices of minority writers are key in the Operation Canada Digital War Diaries Project including the war diary of Edith Anderson (1890-1996) from Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Ontario. Anderson’s original diary has been safeguarded by her family descendants. After her death, they prepared a typed transcription, which served as our copytext, taking readers into her daily activities at the Base Hospital 23 in Vittel in northern France. This hospital unit had been organized by Westchester County Associated Hospitals in Yonkers, NY, Anderson having trained in the United States after being denied access to nursing schools in Canada because she was Indigenous. Today, her diary shares her daily routines of caring for patients, reporting her increased load after going on night duty for two weeks, on June 6, 1918: “Had a busy day to-day and went on night duty. Had fifty-seven patients and three German prisoners to take care of.”

Ten days later, still on nightshift, one of Anderson’s young patients with whom she had become friends, Earl King, died, leaving her deeply affected: “Had hemorrhage at 3:15 A.M. The poor boy lost consciousness immediately. My heart was broken. Cried most of the day and could not sleep.” Two days later she reports going to his funeral: “Came off night duty this A.M. Did not go to bed at all. Went for a bath then sat in the park with Jean Carruthers and wrote letters. The weather was doubtful with showers of rain and then sunshine. After dinner went to the florists and ordered flowers for my boy who died. At 3 P.M. went to his funeral. It rained through the whole ceremony and my feet were very wet, but I didn’t mind I paid my last respects to Earl. Retired early this evening as I had to report for duty the next day.”

Besides these overseas diary accounts of crises, pain, and human connection, the Operation Canada Digital Diaries Project collects and makes accessible home-front diaries written by women and men in urban and rural settings in Canada. Illuminating the civilian experience of the war from the perspectives of home-front preoccupations, these diaries inscribe both trauma and patriotism along with minority writers’ hope for integration and recognition through involvement in the war.

One of the featured home-front diarists, Ella Isobel Rogers (1900-1963), kept diaries through her wartime teenage years, documenting her circumstances maturing into adulthood in the rural community of Hopewell Hill, Albert County, New Brunswick. Rogers was active with the Red Cross and other organizations that supported the war effort and often recorded her attendance at fundraisers and recruitment events. A survivor of the Spanish flu pandemic, she details its devastating effects in her diary, as on October 4, 1918, when she notes: “The school closed Wed. to prevent influenza from spreading if it should hit in the place. There are about 25 cases in Hillsboro. One woman died”. The rhythm of her observations reflects the rhythm of the pandemic, eerily similar to our own COVID-19 experience, with its multiple waves and the efforts at building resistance and resilience.

Read the entire article (PDF 10.6 Mb)